Why do so many safeguarding referrals from schools end in ‘no further action’, and why is the system increasingly ‘fraught and difficult’?

Tes investigates:

Cases stepped down ‘without rationale’

John Spring, national safeguarding director at E-ACT Multi-academy Trust, which has 28 academies across England, says it feels as if there has been “a shift” in the last two years, with more referrals starting to come back classed as NFA.

Cases are being stepped down in status, for example from Child Protection to Child in Need, “quite quickly and potentially without full justification or rationale,” he says.

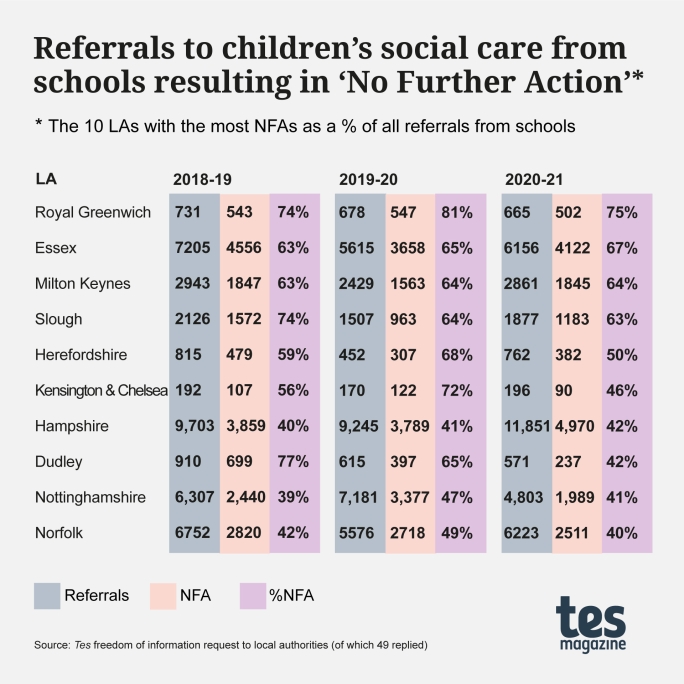

One in three of the 49 local authorities that responded to our freedom of information (FOI) request said at least a quarter of referrals from schools to children’s social care resulted in NFA.

Some councils have pointed out (see box, below) that the NFA outcome does not mean that the case has not been investigated - it can lead to a child being referred to voluntary support such as Early Help, or assigned to cases already known to the authorities, for example.

But other experts warn the high rates of NFA are a real concern. There is a consensus that one of two scenarios is occurring: the LA disagrees with the school, which would be a concern as the school will likely be much closer to the situation and know the child better; or the LA is already involved but the school has not been notified, which is a concern because it means communication lines are not working.

Fears that the child safeguarding system is not working properly have grown in prominence after last year’s front-page stories about the tragic deaths of the toddler Star Hobson and six-year-old Arthur Labinjo-Hughes, who both died in 2020 at the hands of their carers.

A Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel inquiry earlier in the year highlighted “weaknesses in information sharing and seeking within and between agencies” and “a lack of robust critical thinking and challenge within and between agencies”.

And the frustration of those working in schools was articulated in a report published last month by the Department for Education, which found “a sense among some educators that they were powerless and that their professional judgement was not valued by children’s social services”.

‘Significant’ time spent on escalation

Schools and trusts are able to challenge local authority decisions via an escalation process, and this now comprises a growing part of safeguarding work, says Spring. “We’ve never seen the numbers of escalation that we’ve received this last academic year,” he says.

E-ACT has two regional safeguarding leads - one in the North of England and one in the South - and has developed its own escalation policies.

“We are in the position now that we have a really good process,” says Spring, “but the time it takes for our academies to challenge, escalate and chase is significant”.

The trust now separates its referrals to social care into “urgent” and “other” because of the increase in NFA outcomes.

In the school year 2021-22, the trust, which educates 18,000 children, made a total of 870 referrals to social care, of which 61 per cent were accepted. Of urgent referrals, 96 per cent were accepted.

Local authorities ‘bled to death’

Hugh Greenway, CEO of The Elliot Foundation Academies Trust of 32 academies, says he does not want to “point the finger at local authorities” because they have been “bled to death” of resources.

But what he calls the “studied and deliberate” underfunding of local authorities has, he says, transferred “a massive responsibility to multi-academy trusts and schools to add additional processes to mitigate the additional risks”.

“We are taking a greater burden of advocacy on behalf of the vulnerable,” he says. But trusts and schools are “neither funded nor supported” for this work, he adds.

National figures suggest that the number of safeguarding referrals from schools to councils has surged.

In 2022, the latest year for which figures are available, there were 129,090 referrals. This represents a significant increase after a dip in numbers in 2021, where just 81,180 cases were referred. In 2020, the figure was 117,010 cases.

But “exhausted” social workers are unable to respond to this rise in referrals as they want to, says safeguarding consultant and former school nurse, Sharon White.

“Our workforce has diminished in the last decade…social workers have got more caseloads than ever and worse complexities than ever,” she says.

The latest government figures show that 4,995 children and family social workers employed by local authorities left between October 2020 and September 2021, up 16 per cent on the previous year and the highest number in five years.

Full-time equivalent vacancies stood at 6,522, up 7 per cent on the previous year and also the highest in five years.

And the pandemic has made casework more complex, says Heather Sandy, chair of the Educational Achievement Policy Committee at the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS).

“We are increasingly seeing children and families we have not worked with before present to children’s services with more complex and overlapping needs, likely as a consequence of the pandemic,” she says.

The resulting capacity issues mean that school staff and leaders can struggle to get a return phone call from social services and instead have to keep children on-site “late into the evening”, says Dr Mary Bousted, joint general secretary of the NEU teaching union.

Pastoral teams are “already very overstretched” and school leaders, “who already provide much more than just academic support”, are feeling “frustrated and concerned” by the situation, she says.

Referrals process ‘fraught and difficult’

“It’s clear that the safeguarding framework within local authorities is under severe pressure,” agrees a designated safeguarding lead for one of the largest academy trusts, who asked not to be identified.

They add: “Across the multiple local authority areas we work, we can see that council support has been declined for a pupil or family, even when the school’s concerns meet published thresholds…Too often, where support has been agreed, it’s neither timely nor effective.”

This means “the referrals process is becoming increasingly fraught and difficult”, and schools’ safeguarding work “has become even more intensive”, they say.

But how can the system be improved, beyond extra funding for children’s services?

Ann Marie Christian, former social worker and safeguarding expert, says schools and trusts need to ensure they are packaging their referrals effectively so that they meet the thresholds.

And Sandy, of ADCS, stresses the importance of safeguarding training for schools, whose importance in multi-agency safeguarding responses “cannot be overstated”, she says. Of course, she points out, not all referrals to children’s social care will result in a statutory social work assessment.

But as referrals rise in volume and complexity, training is unlikely to be enough to solve the problem.

The wider issue, according to many leaders, is the position that schools are being put in as the services around them creak and strain.

“It feels like a good proportion of the work we’re doing is actually a different function beyond education,” says Spring, speaking for many of his peers.

“We’ve never done as much from a social work perspective as we’re doing right now,” he adds. “There’s no question about that.”

Merrick, who spoke to Tes before leaving headship to become diocesan schools commissioner for Lancaster last term (autumn 2022), calls for a shift in the “perception that schools have the capacity [and] the protected budget” to do everything.

He adds: “We need to safeguard children properly and if that needs investment or expansion of provision, that’s what needs to happen - and I hope that that’s recognised.”

What does NFA mean?

There is no statutory definition of what a no further action (NFA) outcome actually is, and it can vary from authority to authority.

After a referral, children’s social care services often offer advice and signpost schools to other agencies, meaning an initial assessment has been carried out and the case has been deemed not urgent enough for statutory social work intervention.

Some children are supported through Early Help, a voluntary framework that depends on the consent of the family to work.

Following this process, the outcome of the referral may be classed as NFA.

Some councils, such as Kensington and Chelsea, responded to the Tes FOI saying that, in their system at the time, the data collected did not differentiate between mere “contacts”, which required no action to be taken, and true referrals.

Other points raised by local authorities that responded to the Tes FOI include:

- Referral responses are audited and reviewed.

- Help and guidance are provided before the case is classed as NFA.

- Triage process helps to determine the appropriate action.

- School referrals are passed to specialists.

- Many referrals do not require social work assessment.

For further details and to see the report in full, please visit: Safeguarding pressures leave heads 'sick to the stomach' | Tes

Credit: TES Magazine (6th January 2023).